New tool could help track climate change

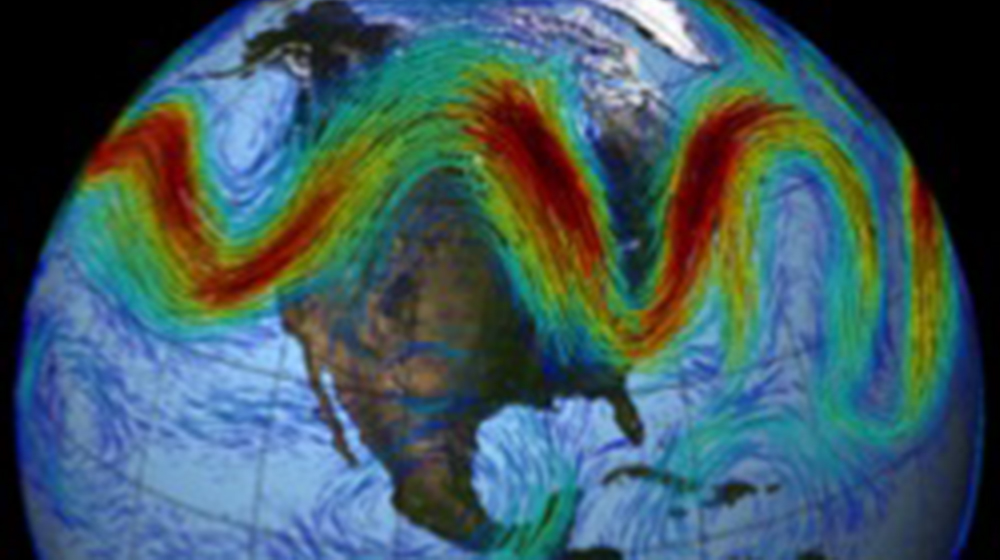

The jet stream currents move in something called Rossby waves—and Loyola assistant professor Ping Jing, PhD, is studying how climate change is affecting their shape. (Image credit: nasa.gov)

By Anna Gaynor

Loyola assistant professor Ping Jing, PhD, deals with some pretty lofty topics: climate change, air quality, extreme weather events, and the movement of atmospheric waves, to name a few.

And now, with a $171,000 grant from NASA, she’s working to help people understand how all of those areas interact.

Jing was one of 25 researchers across the country to receive a NASA grant to create straightforward rating tools to measure the effects of climate change—and to look at the success of actions being taken to fight it. Her proposed Rossby Break Index will show how climate change can alter weather patterns and the atmosphere.

“The general public has learned that the impact of climate change on extreme weather events is that they are going to become more frequent and more severe,” said Jing, who teaches in the Institute of Environmental Sustainability. “But up until now, it is still not very well understood how this happened. Why we will have more droughts, heat waves, and flooding? How can we have both flooding and a drought?”

A complicated combination

Jing wants to look at the jet stream, which are the winds about six miles above our heads. For the most part, they are the ones that transport the earth’s surface weather systems. So, if a predicted morning thunderstorm doesn’t come until late afternoon—the jet stream is the one to blame for its late arrival.

“Our winds generally blow from west to east over North America, but they do not blow west to east in a straight line,” Jing said. “Instead, winds tend to take on a wavy shape.”

The jet stream currents move in something called Rossby waves—and Jing wants to see how climate change is affecting their shape. Sometimes these waves start dipping too far south or too far north. Much like an ocean wave that gets too high and breaks, these atmospheric waves can be pushed so far out of their normal path, that the wave breaks and creates an entirely new pattern.

“If there’s a change in the pattern of the Rossby wave, then there will be a change in the jet stream,” Jing said. “Then there will be a change to the surface weather pattern—so they are linked.”

In addition to weather events, Rossby wave breaking can lead to more high ozone events in cities with high elevations like Denver. This is because changes in air patterns aren’t just happening horizontally—the atmosphere is vertically dipping toward and away from the earth as well.

“Ninety percent of ozone is in the stratosphere—where it is considered to be good,” Jing said. “It’s protective because it absorbs UV [ultraviolet light]. But if you inhale ozone directly, then it’s bad because it’s a very strong chemical.”

Bringing change

By studying three decades of meteorological data, Jing hopes a better understanding of Rossby waves and their effect on weather and atmosphere will allow her to develop a simple color-coded index for high ozone days. For her, addressing climate change requires two approaches: mitigating the damage being done and adapting to what’s happening now.

“If we want to be prepared for climate change, how we are going to prepare for the future weather conditions is important—from a regional level to the local government level to perhaps an individual household level,” Jing said “Do we need to be preparing for more floods, more droughts, or both?

“That means structures need to be ready. That means that power lines need to be ready. That means people’s basements need to be ready. That’s my opinion, so I feel like my research results will help these decision makers to decide if this is necessary, and if this is necessary, then how we should prepare.”